When I was in fourth grade, we attended a program, grade by grade, in the school’s small auditorium, The Little Theater, to learn about telephone etiquette. Sounds downright Paleolithic in these days of constant discourteous smartphone use.

Telephone communication continues to have both an aesthetic and historical place in moviemaking. Johnny Lobo is condemned by a telephone phone call in Scarface (1932). In early talkies audio was sometimes blocked on a phone to accommodate the primitive sound design. But in the glossy sound design of the 1983 Scarface remake—where “f__k” is amplified 226 times in phone calls and dialogue throughout the film—Lobo is again condemned by the same telephone call because telephone conversation continues to provide plot exposition, characterization, and tension in the movies. Where would Wes Craven be without menacing phone calls?

In 1930s Italy, “Telefoni Bianchi,“ a school of moviemaking, was named for Hollywood’s 1930 film comedies that featured white telephones as a status symbol of bourgeois wealth in their Art Deco sets. The gritty Neo-Realist movement of the late 1940s was a reaction against this telephone genre.

In 1940s Studio System Hollywood, Sorry Wrong Number revolves around bitter invalid Leona Stevenson overhearing a phone exchange planning a murder. Leona has only the telephone to prevent the crime.

911 and police-line ties to horrific crime today mean that Jordan Turner of 2013’s The Call has a more powerful phone system to fight a more powerful network of crime—alone.

Can you hear me now, Halle Berry?

In the 1950s, Phone Call From A Stranger builds each of its three cinematic episodes around a telephone call. Bette Davis in the final episode, co-starring then-husband Gary Merrill, steals the film. During her adulterous holiday, Marie Hoke had gone swimming in a crystal clear lake in the lush woods. As she surfaced from her perfect swan dive, she hit her head on the bottom of a massive wooden raft and was permanently injured. But the caller—and the audience—learns this only after the caller goes to visit Marie.

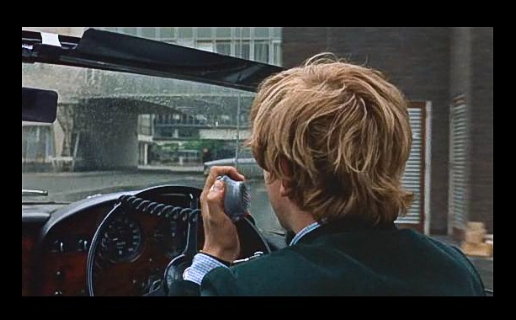

In Blow Up, the 1966 masterpiece, “Photographer” Thomas makes phone calls to his publisher about the blow up the photographer fashioned of a murder in the park…was there a murder? ...Did he take a photo? ...Thomas creates the blow up begging the existential question: If a murder happens and nobody sees or hears it, did a murder happen?

Telephone equipment has improved, not so Robert Blake’s discomforting telephone etiquette in Lynch’s Lost Highway (1997). Although Stu Shephard in Phone Booth (2002) would be hard pressed today to find a pay phone, being held hostage on the phone is an all-too-familiar contemporary situation because our reliance on the phone has increased geometrically as has the telephone’s power to communicate. And since electronic technology will continue to evolve and improve, “telephone” communication will remain movie-friendly. “Telephones”—however improved and re-imagined—will still be employed as plot devices and suspense builders on screen because as plot device technological communication (and miscommunication) can be frustrating, tragic, amazing, and fascinating.

Consequently, the remake “Sorry, Wrong Tweet” could be just as terrifying as the original with the tag line: “Text along with Sarah Jessica Parker in her most terrifying and challenging (read: no Spanx, no mascara) role!” An updated remake titled “Text From A Stranger,” could now address three calls initiated from a plane, voice mails, and dropped calls that are now part of everyday telephone communication.

No one could have foreseen the expanded artistic and lifestyle influences of the telephone in that long-ago Little Theater presentation. Today as we continue to see more sophisticated telephone technology used on the screen, we also use that same technology throughout our movie experience offscreen. We text, confirm the casts, buy our tickets, call our Ubers, and send ourselves reminders of show times on our phones. Bottom line, telephones have now become fundamentally significant to cinema: We watch movies on our phones; we make movies with our phones. This technological and aesthetic evolution drives the movies. We can marathon-watch the Bourne movies and enjoy widescreen images of David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia on our smartphone screens at the beach. Tangerine was shot with three iPhone 5 smartphones and premiered at the 2015 Sundance Film Festival. The new motion pictures indeed resonate loud and clear…even when there is no one in the darkened multiplex to hear it.