Long ago, when I was growing up in Chicago, our landmark department store, Marshall Field’s, was a glorious storehouse of dreams. There was even a covered pedestrian bridge directly into the store from the Wabash Avenue “El” station (El for Elevated or “L” for Loop, I am never quite sure). Inside was a Tiffany-mosaic vaulted ceiling crowning…multiple atria…floors of glamorous departments…every toy and game on display on one sprawling floor…chocolates, confections, and specialty sweets in mountains on another beneath, and a collection of exotic gift items—unique crystal, marble, and silver ornaments from around the globe adorning the ground floor. Shopping there as a kid was like a trip to an amusement park.

For my twelfth birthday, my grandmother took me to the third (as I remember it) floor Book Department and told me I could select any book I wanted as a present: I choose a volume of F. Scott Fitzgerald. The Scribner’s book jacket was green—I still treasure the book today. In my life, Fitzgerald is without peer. I have read The Great Gatsby every year on my birthday since I first read his masterpiece. I treasure the congratulatory note I received from Scottie Fitzgerald on taking my PhD. I burned up the web on the possibilities that I had found (and purchased) the wooden shutters from Fitzgerald’s home at Belly Acres in Encino, CA, where he worked on The Last Tycoon. I wrote a dissertation so I could write about him. Over a five-year period, I counted and categorized—this research predates computer searches—all the words in two of his novels (one and a half, actually) to investigate why Fitzgerald’s prose, the most visual in our language, is somehow static as motion picture.

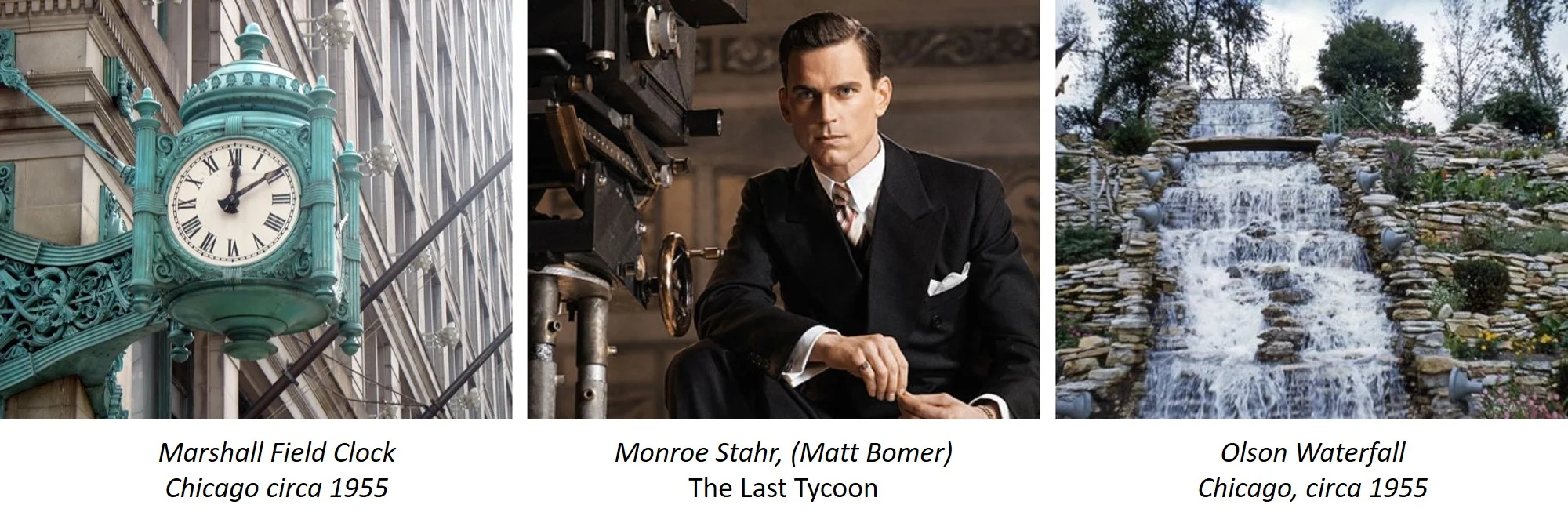

The Last Tycoon, Fitzgerald’s unfinished last novel, is going to be a series on Amazon. Green-lighted. Billy Ray wrote and directed the pilot—I was impressed by Ray’s work when I saw his Shattered Glass in 2003; critics were generally put off by the Amazon pilot episode: and a respected colleague called to tell me he had screened the pilot and admired it. Three for three…I was preordained to like it.

This single episode is more extrapolation than adaptation. Most pertinent details of the novel have been altered, almost everything that is subtle in Fitzgerald has been spelled-out, upper case, in neon, and most effectively, the historical reality of Fitzgerald’s fictional universe, not the incidents of his plot, has been staged for the camera. The pilot is an unfinished adaptation of an unfinished book. Somehow this lack of closure makes the single episode seem strangely reflective of, and as, a work in progress.

It is Fitzgerald’s coup that all his movie adaptations are opulent—no exception with this pilot. But this pilot is his coup d’état. The Depression era story glorifies the 1930s, so we are spared an arcane 1920s sing-a-long soundtrack and tiresome sequences of madcap “flappers” dancing in fountains. Meticulous in every detail of the production, the decade never looked better or sounded more lush as underscored by the pilot’s brooding sense of destruction just round every sumptuous corner. Hoovervilles at the gate. Suicides on the set. Nazis in the board room. Casting is great—Dominique McElligott is dazzling, Kelsey Grammar can act, and Mark Bomer not only understands Fitzgerald, he is handsome as hell. Finally a hero for Fitzgerald, epic, beautiful, and dangerous. Bomer channels Monroe Stahr as well as he channels Stahr’s alter ego and creator, Fitzgerald himself. Monumental things are happening beautifully all around him–are they real? Sure. His gorgeousness is their reality—and so every hyperbolic incident in this flamboyant production has grace—just as every gorgeous word has in the Fitzgerald novel.

At Tycoon’s Writer’s Ball on screen before Stahr dances with the exquisite Kathleen to perfect music reducing the perfectly elegant ballroom set to mere window dressing and gets his face slapped by a crazed widow to boot—looking absolutely perfect in his white tie and tails, during perfect table conversation with his boss’s daughter who is in love with him among a bunch of writers in street clothes, Stahr reveals, “ I like people and I like them to like me, but I wear my heart where God put it—on the inside.” What? What did he just say? The guy is a walking, talking literary trope. And who the hell looks like that? Who sounds like that?…Who?...obviously, F. Scott Fitzgerald.