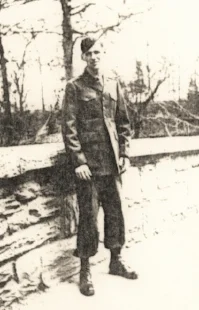

My father at 17 at Parris Island, SC.

As a date that has been cursed to live in infamy, December 7th was an actual date when real people across America must have felt exactly what we feel today when our newsfeeds and social media and TV networks cover terrorist attacks. But in 1941, the world-at-large was more mysterious to people…it felt larger and more unknown than it does today. For us, any “breaking news” is met with immediate onsite cameras and realtime reports. In 1941, reports of the Pearl Harbor attack were limited to scratchy reports on the radio or fuzzy newswire pictures a day later.

Below is my father’s remembrance of that day and its impact on his, his family’s, and his friends’ lives. He wrote this remembrance years later, but years ago, too.

[Please note that his use of the politically incorrect and offensive “Japs” is only a reflection of the mindset of 1941: the Japanese had immediately become the hated enemy and American society was consumed with that hatred. I must disclose that by the 1960s, we lived next-door to a Japanese family and my father related to them with common, neighborly decency.]

I was about a month short of my 16th birthday when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. I lived with my parents, sister, and brother in Southwest Philadelphia. My brother, Bill, and I had been to a big high school football game that Sunday, December 7, 1941. Upon returning home we were told the news. We gave a kind of, “What’s a Pearl Harbor?” reaction. Neither we nor any of our friends had ever heard of it. But of course, we knew it meant war. This was of great interest: Germany and Italy took a backseat, now…all was Japan. The sneak attack made them easy to hate and sad to say, even the comics portrayed stereotyped buck-toothed, bow-legged, little men…the enemy.

The following day was declared a holiday from school…not because of war, but because of our football victory for the state championship! As a result, I was at home and heard on the radio President Roosevelt’s declaration of war. It was his “date which will live in infamy” speech.

Frank Conlin in his "shiny black jump boots."

The war became the prime influence in young men’s lives. I was no different than the rest. I lost interest in school, dropped out about May and started talking about joining the Marines. Frank Conlin, a neighborhood friend, was the reason for my interest in the Marine Corps. He—like many others—had enlisted soon after Pearl Harbor. He became a paratrooper and when I first saw him in uniform with his shiny black jump boots and silver wings, wow!

I took a job with Sun Shipbuilding Company in Chester in July as a shipfitter’s helper and worked on tankers that had been hit by the enemy and needed repairs.

Frank was stationed in North Carolina and was home quite a bit. We would go out together and I thoroughly enjoyed his stories and plagued him with questions. Once I asked him, “Do you really holler, ‘Geronimo!’ when you jump?” He thought for minute and said, “The Army hollers ‘Geronimo!’ Marines holler, ‘Here we come you Jap bastards!’…or something like that.” This enhanced my admiration for him and the Corps and I was itching to go. I had definitely decided on the Marine Corps.

Frank was the main reason I ended up in the Corps but there were other reasons, too: the movies I saw and the books I read. No sooner had I read about the Marines in Guadalcanal Diary by Richard Tregaskis, than Frank came home with a direct connection to Guadalcanal: an officer who had served there asked Frank to deliver something to his girlfriend on the Main Line. Frank asked me to go along. The house was magnificent and the landscaping beautiful; a maid met us at the door; down a sweeping staircase came this beautiful girl. She stopped halfway and greeted us. I was intrigued…it was like a movie…her name was Mimi and it fit! She was the essence of the Philadelphia Main Line. I was so young and unsophisticated that I associated that visit with the Marine Corps…I thought all Marines’ girlfriends were like Mimi on the Main Line. What a wonderful organization and I had to become part of it…I was seventeen. I began to bug my Dad to let me enlist early.

A small command of Marines on Wake Island, a tiny Pacific island, had been attacked by an overwhelming force of Japanese. Before the island fell, the story went, the Marines received a radio message asking what they needed. “Send us more Japs!” was their supposed reply. If that didn’t rouse a young man’s patriotic fever, nothing could. I pleaded with my father to sign for me to enlist at 17. My mother had died of tuberculosis the preceding year; had she still been alive, I probably would not have gotten permission. But in the climate that prevailed then and the fact that my father felt that he had “missed” serving in World War I, my pleas were working. But my father warned me, “If you don’t like the Marines, you can’t just come home, you know!?” He was dead serious. I told him, “I may be naïve, but I’m not that naïve.”

On November 30, 1943, I went to the Custom House to join the Marines. I was thrilled as I filled out the forms and was given the physical. I remember how nicely I was treated…and why not? I was probably just what they were looking for: 17 years old, six feet two inches, 180 pounds, and rarin’ to go! After being sworn in, I was “assigned to active duty on a non-pay status.” The officer in charge gave me what he said would be my first “order” in the Marine Corps. I almost snapped to attention. He reached into his pocket, handed me a dime, and said, “Go across the street and get me a Coke.”

My father on leave October 1944.

I ran all the way. When my mission was complete, I was given the “necessary street car transportation”—an 8-cent trolley token—and sent home to await further orders. On December 16, I was put on pay status and instructed to report to Parris Island, South Carolina. I left by train from the B&O station where my father and sister saw me off. My father’s parting advice, “Be a good boy and remember the sacraments.” I can only imagine how he felt.

I arrived at Parris Island—what the media called “A United States concentration camp”—at 3:00 on a damp December morning in 1943. Finally, I was going to war.

For the record, Corporal Francis P. Conlin Jr. was killed on Iwo Jima, March 10, 1945 at the age of 23. My father served on the battleship USS Texas and participated in the D-Day invasion of Normandy, the Cherbourg bombardment, the invasion of North Africa, and the island battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa. He was home for Christmas 1945.