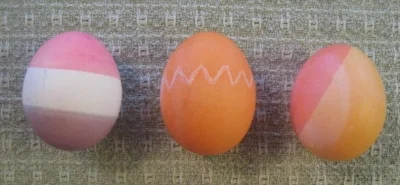

For many of us, Easter season includes the annual ritual of dyeing Easter eggs. But a few years ago, our family began to “color” Easter eggs, which included traditional dyeing, but expanded to include painting them with food color. The variety of colors available by dyeing is significant—colors changed by length of time in the dye, number of colors applied to an egg, assorted shapes of the color applied (e.g., half the egg one color lengthwise or heightwise or diagonally), and the dynamic wax pencil used to write on the undyed egg), but by using Q-tips or paint brushes with undiluted food coloring, the possibilities seemed infinite!

When I was a child, PAAS made the obligatory egg dyeing kits: color tablets, wire egg holders, and punch-outs in the box to hold the eggs as they dried. We cobbled together assorted teacups, dropped each tablet into a mixture of vinegar and boiling water, and the dyeing began. Even though I was proud of my own creations, my father or mother always seemed to create the year’s best egg. Over time, PAAS expanded their dyeing options—marble, egg stamps, and overlays…moving the whole tradition further away from the religious symbolism it first offered. Originally, egg dyeing was limited to red—to symbolize the blood of Christ; on the hard shell—to symbolize the tomb; and, of course, the egg inside—to symbolize rebirth. Like most religious traditions, it lost its religious significance and devolved into a secular entertainment.

Once my family began coloring eggs—creating designs well beyond even the newest PAAS product—suddenly my imagination burst wide open. Easter eggs could be as varied and exciting as my talent and patience would allow.

We created patchwork eggs, polka-dot eggs, striped eggs (up-and-down or side-to-side), graphic designs, disguised eggs (e.g., globe or watermelon), even eggs that became characters! Our experience of Easter changed. Hiding the eggs and finding them on Easter morning adopted a kind of specificity, because they were no longer just blue or red or yellow eggs: “Where’s the globe egg?” “Where’s Mr. Egghead?” “Where’s the kitty egg?”

Each Easter egg became a kind of self-expression, a nexus of imagination and talent and patience. First, we had to imagine what the egg could become; next, we had to plan the design; and lastly, we had to produce carefully, patiently, precisely to make it work. It was always great fun to spend the evening as a family, each of us delving into his/her psyche to find a new self-expression.

But even with all this fun and self-expression and change, I miss the Easters of my youth, when religious ritual reinforced my faith. I was an altar boy and served Mass on Easter mornings, which meant lighting lots of candles on an altar overflowing with lilies. The weeks before had included the Stations of the Cross each Friday…for my young self, it was actually awesome: stopping in front of each of the 14 stations; incense swirling; struggling to hold the cross correctly when I was the crucifer or to hand the thurible to the priest and take it back at the right moments; the priest reciting prayers at each station, creating a kind of reverie of repetition. I looked forward to Palm Sunday with the reading of The Passion, even in all its length and graphicness, except when Easter came late in the calendar—back then, the church was not air conditioned so it could be stifling and standing for the whole story became a kind of suffering all my own.

For me, the tactics have changed, but Easter remains a time of expressed faith.