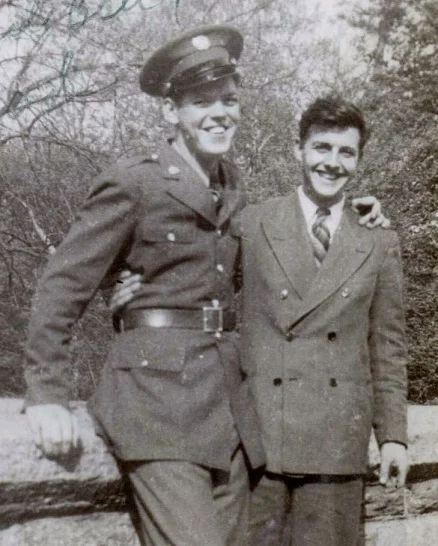

Ignoring the dangers of a world at war (L to R): Jack, Frank Conlin (home on leave one year before being killed-in-action on Iwo Jima), Mary, and Jerry, March 1943.

In Kay Square Press’s latest release, A Philadelphia Family Goes to War, day-to-day life during wartime is exposed in detail; but one interesting feature of the letters is what is not said, what is implied behind the words on the page. The correspondents reach out to each other across thousands of miles in a steady stream of hundreds of letters that take days, sometimes weeks, to arrive; yet, so often they don’t actually say what they mean.

The letters are filled with mundane facts—chatter just to stay in touch: Dad’s stiff shoulder, Bill’s bad feet, Pop Pawley’s fall on the ice. Commonplace information fills the pages: requests for writing paper, pens, razors, and candy; discussion of sports—football, baseball, and boxing—in June 1945, Dad writes, “I guess you know the A’s & Phils are in their usual place (Last place)”; and opinions about movies, radio, and music.

Ignoring the dangers of a world at war: Mary and Jack (home on leave six months after the Normandy D-Day Invasion), October 1944.

The boys at the front lines—Bill in New Guinea and Jack on board the USS Texas—are allowed to tell only a few facts. The censors keep them from giving details; at times, they aren’t even allowed to tell where they are. Thus, details about invasions or battle action are delayed for weeks and months. In June 1944, four days after the D-Day invasion of Normandy, only a form letter drafted by the ship’s chaplain was allowed, which Jack sends to his Dad. The letter mentions “unpleasant sights,” but focuses on successes and camaraderie, not the dangers:

“There have also been many unpleasant sights, but I won’t tell you about those now. At one time, we had 27 enemy prisoners on board…didn’t look like supermen to me. We also had 29 U.S. Army Rangers aboard... Their wounds were treated on board, and only one died…

We have been under attack by enemy planes and glider bombs at night, and have seen many planes go down in flames. There have also been shell splashes in the water fairly close to us … and most of us consider ourselves lucky…

This experience has drawn us closer together on the ship, and has shown us what a fine bunch of ship-mates we have. The Army has praised our shooting, and we are very proud of the knowledge that we have done a good job.”

Ignoring the dangers of a world at war: Bill (home on leave one year before shipping off to New Guinea) and Jerry, March 1943.

When the boys get to describe their experiences at the front, they minimize the danger. In June 1944, from the jungles of New Guinea with the Sixth Army, Bill writes home:

“I am able to tell you only that we are really in it now, things are not as bad as they maybe and as yet our outfit has not seen any Nips but they are not over 2000 yds. away and at nite they come right up to our area. Fox holes and slit trenches are standard accessories with every outfit now. Second nite we were here a Jap plane came over & dropped a few but none were close to us.”

Both letters end with the same phrase, a phrase that the boys send home more than 50 times in their letters: “don’t worry about me.” The words say, don’t worry, but they mean—they imply—that the boys know the family worries constantly! They never really acknowledge the dangers they face; they never acknowledge or give credence to their family’s worries; but the implication is clear: “I know you’re worried about me.”

Similarly, Dad and Mary back home wait anxiously for each letter as a sign that their boys are alive and well while far from home. Neither one ever says, “I think you’ve been wounded or killed when I don’t hear from you.” They write only that it’s been a long time between letters…”haven’t heard from you” is as expressive as they get. They use the phrase frequently, as if the boys couldn’t write often enough. Except on January 31, 1945, when Dad deals with the kind of news that frightens him most; he writes to Jack:

“Last nights Bulletin told me about two sons, one killed one wounded at the same time, the only children of Herb Clark who I worked with for years… Things like this kind of get a fellow down a little, especially when he hasn’t heard from his boys in a long time. But I know that everything is OK. It just has to be!”

Of course, Dad is implying that Herb Clark’s tragedy may be his own any day soon. Yes, it gets “a fellow down,” but he never actually writes the words to describe his fear, he never writes: “you and your brother could be killed at any time.”

Then, in July 1945 as the end of the war feels close, Dad writes to Jack:

“…believe it or not I finally got ambitious & started to do some painting & general fixing. The idea struck me about 10 days ago while listening to the news. ...I got to thinking what a shack to have to come back to & call home. So Result! I got busy, so far I painted the bathroom & the stairs. Well when you start to do a little something it always seems you run into more.”

William J. and Anna D. Pawley on their wedding day, April 1920.

Later in September of that year, after the war is over and Dad is expecting his sons’ return, he adds an explanation of his earlier “ambition,” the implied reason behind his efforts to paint and fix up. He had worked—through his constant, exhaustive letter writing—to hold his family together after losing his wife in August 1942; he makes explicit what he had implied in his earlier letter:

“The most important one for help & encouragement is missing! The home is a big problem for me. I would love to have a home that you & Bill would be proud to come back to but unfortunately I am only a man & not a combination of Mother & Father.”

One thing that is never implied, that is always overtly and directly stated, that closes virtually every letter: a bidding of love. From father, sister, soldier, and Marine; from home, from the office, from aboard ship, and from the jungle; handwritten, typed, and V-mail; the letters all close with “love & kisses,” “love to all,” and “love from all.”

Some things are best communicated through implication; some things are best said directly.