© DreamWorks, 1998.

My wife accuses me of loving war movies, as if I watch them only for the excitement. “Dad’s watching another war movie,” she’ll announce to the kids, as if I were mindlessly giving in to some obsession to watch Thin Red Line (1998), Saving Private Ryan (1998), or even an oldie like Paths of Glory (1957).

But when they are well done, war movies tell about the extremes of human experience where a person’s mettle is tested as in no other circumstance. Is there an equal experience to fighting to save one’s own life—literally? Or risking one’s life for others? Or making decisions and taking actions that matter in a life-and-death way—literally? Whether it’s planned actions or spur-of-the-moment reactions, one’s actions and decisions—one’s life—is intensified in war. That’s what I enjoy about well made war movies.

When Captain Miller (Tom Hanks) sits and cries alone—a central moment in Saving Private Ryan—the impact is one of personal struggle to absorb the terrors of war while maintaining focus to lead and lose men on a dangerous, hopeless/hopeful mission. Captain Miller’s moment of emotion underscores his heroism throughout the rest of the movie: he does more than can be expected in leading his men, confronting the enemy, achieving his goal…and in overcoming his fear.

That same intensity of experience is what I see in all real-life veterans that I meet. Look up the word “veteran” in a dictionary or thesaurus and you’ll find that it doesn’t dwell on war or military service; it is about experience, practice, expertise, mastery. When I meet a veteran, I wonder at what they’ve experienced and discovered about themselves; I wonder about their moments of fear and emotion and how they overcame them; I wonder at what they achieved despite their fear. And, of course, I wonder what I would be capable of if I had been put to the same test…

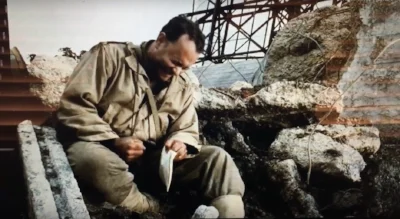

Soldiers clear a bunker in New Guinea, 1944. Bill writes, “you get a little sick & scared & mad as H.”

In Kay Square Press’s latest release, A Philadelphia Family Goes to War (available at Amazon), both boys—one a soldier and one a Marine during World War II—write home about facing and overcoming their fears. While in New Guinea in 1944, Bill writes to his father about the horrors of war and the lure of being home again:

“You see some awful sights, you know we lose men too & when you see some dead boys you know you get a little sick & scared & mad as H. The dead decompose fast here in the heat & rain & it is not a pretty sight to see. You get used to it, but never forget it. Hope this isn’t too gruesome but maybe you can see why it will be nice to be home again where there is nothing to worry about except $$$”

The anti-aircraft fire whitens the water ahead of an incoming kamikaze. Jack writes, “His pendulum-like sway makes him a tough target. Closer and closer he comes…they always look closer. Just when it seems he will prevail, one wing shears off, then the other, he bursts into flames and hits the water in a tumbling splash. There is wild cheering.”

His brother, Jack, a Marine on the battleship USS Texas, writes, too about doing his duty despite his fear. During the battle of Okinawa, the Texas’s anti-aircraft (AA) teams lived and slept at their stations for 50 straight days; on April 6, the Japanese launched an estimated 700 planes—over half of them kamikazes—and exacted a terrible death toll on the US fleet in both lives and ships. When censorship about the battle finally ended in June 1945, Jack wrote his father about the thrill of victory despite being more than scared:

“…my station is still on the AA guns and our gun was one of the three guns who knocked out the particular Jap we got credit for. He was coming very low, heading directly at us, probably a suicide run, when the guns cut both his wings off—was I scared? That isn’t the word for it!”

Jack’s grandson gets a history lesson: standing at his grandfather’s post on the quad 40s anti-aircraft guns on the USS Texas.

In the end, yes, I love war movies…especially when they show what makes our veterans veteran: the experience of overwhelming fear and the exhilaration of overcoming it.